|

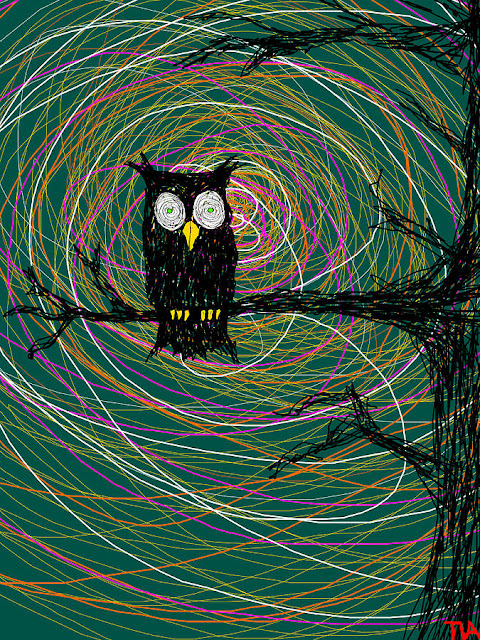

| An artistic shot created by Chris Benchetler in his 2019 film, Fire on the Mountain. | Screengrab from Fire on the Mountain. |

The dozens of canvases cluttered in Chris Benchetler's art studio at his Mammoth Lakes home give an impression as if you had just walked inside a small temple where the walls were melting, oozing every possible mixture of color imaginable. The canvases are all sorts of different shapes and sizes; some are hanging up on the wall, tilted or upside down, while others are stashed away in the corner between boxes of paint and art supplies. A cool September breeze gently sways the pine trees visible from the studio's window. Between balancing time raising two young boys, working on several original art commissions, serving as Creative Director for Atomic Skis, supporting a wife battling cancer, and still finding time to go outside to ski, bike, or climb daily, going to the studio to make art is no small task for Benchetler. Yet, he still manages to find the time and show up every day.

"I view art—and skiing and rock climbing and all the things that I try to do on a daily basis—as a form of meditation. You're looking inward when your painting and you're really expressing yourself in that moment in that space and time."

|

| Chris Benchetler’s Mammoth Lakes art studio. | Photo courtesy of Chris Benchetler Twitter |

The inspiration behind Benchetler's art comes as the culmination of the 36 years he's spent on this planet, with a strong influence from nature, he told me. When I spoke with Benchetler on the phone one fresh autumn morning he was sitting in his backyard under a pine tree, taking a break from painting. The Mammoth Lakes, California, local is best known for his career as a professional skier and his line of Atomic Bent Chetler skis, which he helped create and continues to produce the renowned psychedelic artwork for. He's a master of his craft, having practiced it since the early days of his childhood.

Benchetler has been both a skier and an artist since before he could remember. He has a humble beginning on an alpine racing team as a young child and was always doodling and drawing on his school homework, he says. He entered local art competitions in elementary school, even recalling that once he won a stuffed animal as a prize at one of those contests. At 15, he was a professional skier who would soon appear at the X Games. By 22, he helped launch the first line of Atomic Bent Chetler skis, which have since become one of the most popular ski models on Earth. Now at 36, he's the director and star of several ski films and creator of a myriad of commissioned original works, from public murals to digital art. He's descended extremely technical big mountain lines in places like Alaska with an ease and style that's uniquely his own, often resembling something more of a big wave surfer than a freeride skier. He's also got a van that he once lived in, using it to travel around North America chasing powder. The side of it is painted with his own artwork.

Working with Atomic Skis, Benchetler helped create and launch the Bent Chetler ski in 2008 as his first professional art commission. Every year since, he and Atomic have showcased a fresh layer of signature-style graphics on the latest model of Bent Chetlers, summoning the imagination drawn from a life spent playing in the mountains. Just like with his skiing, his artistic style is uniquely his and is easily recognizable at first glance by almost anyone who skis or snowboards. The flow of creativity never seems to cease, and year after year he keeps bringing to the table new, mind-captivating designs for the Bent Chetler ski and his own artwork.

|

| Chris Benchetler lays out a spin in the backcountry. | Photo courtesy of forecastski.com |

When flowing down a mountain in fresh powder, pillars of white pouring over him as he maintains his speed, Benchetler says he feels a sense of connectedness. This is often where he gets the inspiration for his art, which gives viewers a perception of something flowing: something that is moving and breathing—that is alive. "From the soil to the trees to the plants—everything on this planet is connected," Benchetler told me. "Spending as much time as I do in the mountains has really helped me experience that firsthand."

Benchetler doesn't go out to ski a line because he thinks someone will like it. This same philosophy applies to his artwork. He does these things only to express himself as freely as possible—to push himself further, physically and mentally, without delegating any energy towards impressing an audience. This rids him of any self-imposed handicap, allowing him to express his vision purely.

|

| Chris Benchetler creates his signature ‘Old Man Winter’. | Photo courtesy of Rolling Stone |

Skiing and art provide the same emotions, Benchetler says. When he flows on the mountain, he takes that feeling of flow—that feeling of creative freedom—and applies it to the way he mixes his colors, strokes his paintbrush, and crafts one of his works. That feeling inspired by nature is used to express what is inside of himself in a blend of dripping color. You can physically see this palpable state of flow by looking at any one of his pieces, like the ones incorporating Old Man Winter that show an aged mountain spirit fused together with mountain scenery or ocean waves, with no clear distinction between where one subject ends and the other begins. At the time of our talk, Benchetler was working on several different paint pieces in his studio. Having dabbled with a little bit of everything he says, acrylic is his go-to and he's a big fan of watercolors. "Oils are great, too, but time-consuming."

As an artist, skier, human being—Benchetler believes it's important to never stop learning; to flow with the river of change rather than try and fight it. This mantra is exactly what led him to create his first ever Non-Fungible Token (NFT), or digital artwork, which Benchetler says is just another extension of the art world we live in. "To think back to when the internet was first being developed and all the photographers I worked with that were completely against going to digital cameras and all the cinematographers that didn't want to stop shooting with 16 millimeter, and then technology just happens. There's so much of Web3 that I do not understand, but it would be naive for me to think that it would not be part of our future."

Like the strong theme of community that surrounds the music of the Grateful Dead, which Benchetler has proclaimed his love for via his art and even a Grateful Dead-inspired ski film, Fire on the Mountain, his works are there to inspire whoever looks at them. By illustrating his own mind's eye depiction of the beauty surrounding the natural world, Benchetler believes he can incite in someone else that same sense of wonder. His art is there to encourage and captivate but also motivate.

On his website, there is a line of text that stands out. "When you tap into your mind, the right line always reveals itself…on the mountain and on the canvas." In a world that more and more seems to promote disconnectedness from mind and spirit, there are still those like Benchetler that give a visual snapshot of what tapping into your mind looks like—on the mountain and on the canvas. But there's a secret to this powerful statement. Tapping into your mind and finding your flow, feeling true creativity—it's not only possible by seasoned professionals or the spiritually inclined like Benchetler. Anybody can do it. You just have to be open enough to access it.

New collab just dropped. I put a bunch of my @GratefulDead inspired work on some new @Smartwool merch. Available for a limited time here 💀🌹https://t.co/mGbsJgqbuD pic.twitter.com/SboW9hVHhl

— Chris Benchetler (@ChrisBenchetler) November 14, 2022