|

| Ruidoso's landscape bears the scars of the South Fork and Salt Fires, which devastated over 25,000 acres and 1,400 structures in mid-June. Thousands of residents lost their homes, including some of the firefighters who fought the blazes. | Photo: Martin Kuprianowicz |

Phoenix (noun): in ancient Egyptian and Classical mythology, a legendary bird symbolizing immortality and resurrection, believed to be reborn from its own ashes after a fiery death every 500 years.

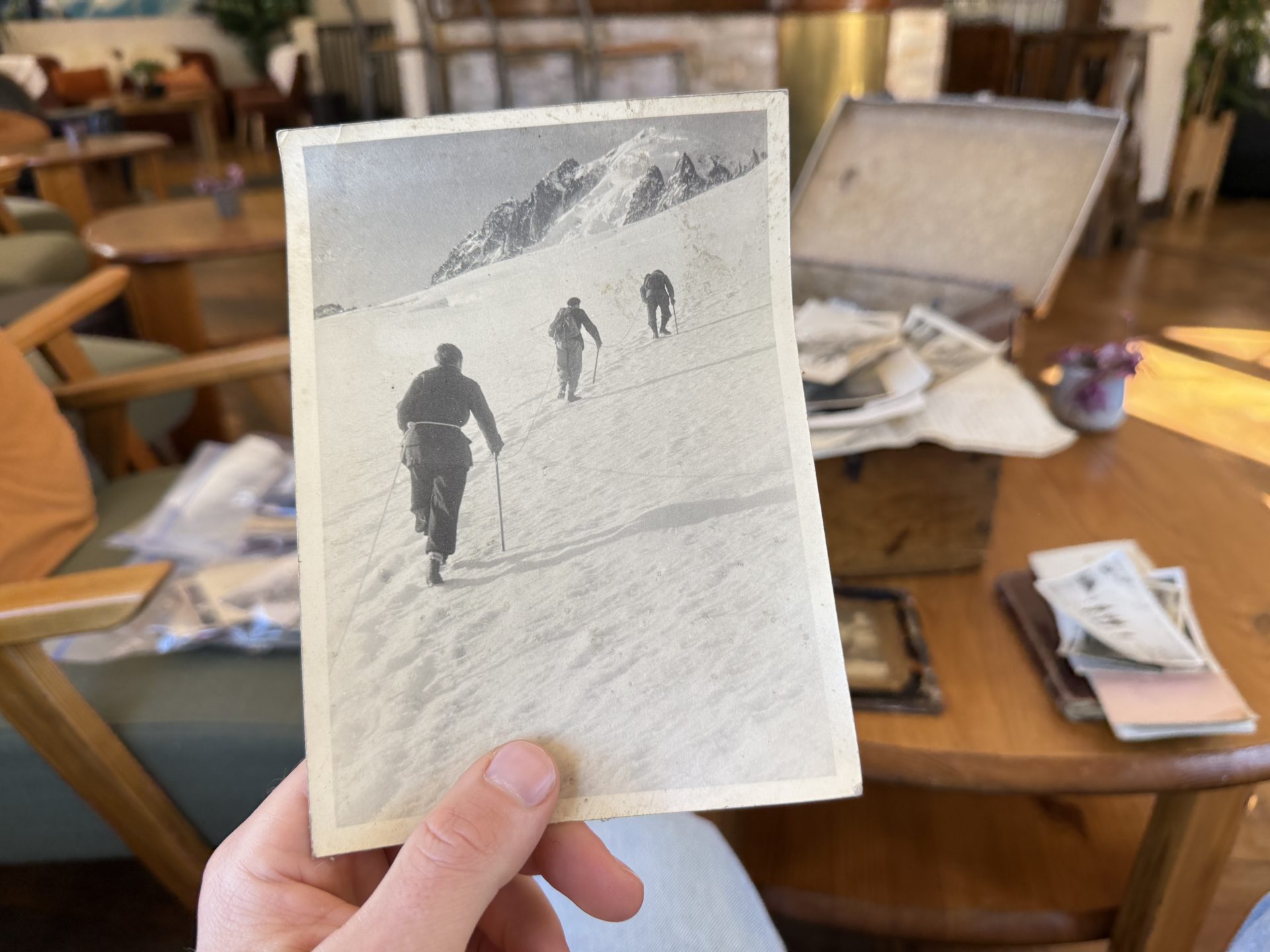

"Nothing left." Those were the two words my father had texted me the night of the Summer Solstice when he confirmed the unthinkable: our home in Ruidoso was gone. Growing up in West Texas, Ruidoso, in south-central New Mexico, was a five-hour drive away, and I went skiing there every weekend with my father from the time I was 2 years old until I moved to Utah for college at 19. Being a ski bum, my father hated West Texas, which had lured him there for work, and we were both in Ruidoso every chance we got. He had owned a property in town for 15 years until it, along with over 1,400 other reported structures, burned down earlier this summer after two wildfires ignited near the town, home to Ski Apache Ski Area. The South Fork Fire was reported on Monday, June 17, at 9:07 a.m. and the Salt Fire was reported later that day at 2:00 p.m. With high winds and plenty of fuel to burn, two massive wildfires had converged on the town from opposite sides; at the time Ruidoso was experiencing its own Perfect Storm moment.

By mid-morning, the sun was blotted out by a thick orange plume rising miles into the sky. At 6:48 that evening, the town's mayor Lynn Crawford issued a mandatory "GO NOW" evacuation order for all of Ruidoso's 8,000 residents. They were told not to go home and collect personal belongings but to get in their vehicles and leave the area immediately. Videos on social media showed flames as tall as ten-story buildings approaching rapidly. "We were at our tattoo shop. We were frantic," Logan Fleharty said, a longtime local and business owner who goes by "Fle" (pronounced, "flea"). "We saw it coming. You could see the fire close—you're watching the fire roar on houses and explode propane tanks." The roads then turned into gridlock. Some residents reported that it took them three hours to drive five miles. Cars were stuck bumper to bumper in a hectic attempt to get out of Dodge while their home was burning.

|

| This photo showing a plume of smoke stretching several miles into the sky was captured by a resident the day the South Fork and Salt fires ignited in Ruidoso. | Photo: Austin Miller |

A smoke report rushed into the Smokey Bear Ranger District on Monday morning from the Bonito Fire Department, a few miles north of Ruidoso, indicating smoke rising from the Mescalero Apache Reservation near the base of 11,981-foot Sierra Blanca, the area's tallest peak. The smoke report was relayed to an interagency dispatch center, which began coordinating resources by contacting various crews and agencies for assets, including fire engines, air support, and wildland firefighter teams known as Hotshots. The cavalry was getting organized. Meanwhile, officials at Smokey Bear went up to the Ruidoso Fire Lookout Tower to get eyes on the blaze. By mid-morning, it had been confirmed: a large wildfire had been started in an extremely problematic area and was heading directly for the town of Ruidoso.

The South Fork Fire started in the northeast section of the Mescalero Apache Reservation in an area known as Upper Canyon, which is a box canyon just a few miles west of town. Upper Canyon is surrounded by steep terrain and has a high concentration of forest fuels like dense swaths of conifer trees and thick shrubbery. It had been previously identified by the Forest Service as a high-risk area where a wildfire could have severe consequences. That, paired with strong winds from the southwest, was causing the fires to burn at an exceptional rate—hundreds of acres an hour. Within 24 hours, the South Fork Fire would have burned over 15,000 acres of pristine forest.

|

| Thousands of homes like this one were destroyed by the South Fork Fire in Ruidoso, which ignited on the Mescalero Apache Reservation on June 17. | Photo: Austin Miller |

By mid-afternoon on the first day, three Hotshot crews were dispatched: Sacramento, a New Mexico unit; Tatanka, from South Dakota; and Ruidoso's own Smokey Bear unit. However, the steep terrain and ready-to-burn fuels made it impossible to charge in immediately. The crews had to devise a tactical plan to enter the area safely, especially with spot fires popping up away from the main blaze. As the fire grew, some locals reported falling ash in the form of burnt clothing and charred chunks of magazines landing on their properties as far as 19 miles away. Southern New Mexico's fire season is from March through July, and with the abundance of fuels and dangerous fire conditions in the days leading up to the fire, the South Fork Fire was no freak occurrence—it was only a matter of time. The factors that set the stage—ripe fuels and strong winds—were such that a significant wildfire was almost inevitable. Crews quickly recognized the need to pull back and develop a safer, more coordinated approach.

Air support began dropping slurry, a red fire retardant, but the high winds and heavy concentration of fuels kept the wildfire growing. Helicopters were using Ruidoso's nearby Grindstone Lake to pick up water to drop on the fire. Even with aircraft darting across the smoke-filled sky, the situation continued to devolve. By the next day, the South Fork Fire had consumed 15,000 acres and over 1,000 structures, killing two people. One person was found in a burned vehicle and another was discovered with burn injuries, according to New Mexico State Police spokesperson Wilson Silver who spoke with NBC News. Air support wasn't making much of a dent initially because the fuels were just too receptive. Firefighters had to balance the necessity to combat the blaze with ensuring the safety of their crews. Then even worse news came in over the radio: another massive wildfire had started on the other side of town.

|

| By Monday night, the South Fork Fire had already incinerated thousands of acres and hundreds of structures. | Photo: Austin Miller |

Enter Salt Fire. By 2 p.m., Ruidoso had two massive wildfires raging on either side, choking the town from opposite directions. At the time it wasn't clear how either fire started, but the causes weren't the focus yet; regular people just needed to get out of the area so crews could get in and fight. As additional support poured in with more fire engines and Hotshots, those resources were now being divided and sent to both the Salt and South Fork fires. The Salt Fire was situated in a more remote area of Ruidoso, with fewer structures in its path, unlike the South Fork which was already burning through Ruidoso neighborhoods like Cedar Creek and Alpine Village. Soon, nightfall would come, bringing with it diminishing winds and more suitable conditions for Hotshots to get in and battle the advancing fires.

By the evening, the town had been completely cleared out and evacuation centers were established at the Inn of the Mountain Gods Convention Center, the Mescalero Community Center, and Eastern New Mexico University in Roswell. Residents were advised to seek shelter with loved ones outside the affected area or at the designated centers. Yet there were a few stubborn locals who decided to stay in the empty, smoke-riddled town and ride it out. They refused the mandatory evacuation. While the order is legally enforceable, forcible removal of residents is rare. Law enforcement typically focuses on strongly urging compliance, documenting those who choose to stay, and potentially restricting re-entry to evacuated areas.

|

| The author parked his vehicle on Ski Run Road where he captured this image that shows how the South Fork Fire spread and devastated thousands of acres of once pristine forest. | Photo: Martin Kuprianowicz |

"No one was forcing us to leave but if we left we wouldn't be let back in because of the evacuation order," Fle said.

Fle is a 39-year-old tattoo artist and co-owner of a local tattoo shop, Scorpion Tattoos, who grew up in Ruidoso and didn't evacuate when he heard the order. He's about six feet in stature with medium-length, wavy almond brown hair, light green eyes, a friendly face with big nostrils, an outgoing, charismatic demeanor, and lots of tattoos. When I spoke with him in mid-July, almost a month after the fires were contained, we were sitting in front of a mural he painted inside of Downshift Brewing on Sudderth Drive. The mural portrayed a colorful scene of Ruidoso: a short blue and white camper with the door open revealing a disco party inside of it which was placed in a field amongst green ponderosa pines and wild raspberry bushes; there was a mountain biker and a happy hiker, the changing fall colors of aspen trees, a campfire at the edge of a mountain lake, and a skier going downhill—all at the forefront of Sierra Blanca with a bright yellow and red Zia hovering over it, an ancient Pueblo Indian symbol for the sun and the state icon for New Mexico. Fle told me it was a work in progress and that he wanted to add a few more features before he was through with it, like some raver raccoons partying under the disco ball in the camper.

When the fires first started spreading they quickly wiped out the cell towers, rendering Ruidoso a dead zone. Only Hotshot crews with radios and satellite communications systems could communicate with one another on the first day—except for Fle, who realized he had something that could play a key role in keeping the community connected. "All the cell phone towers went out. Dead silence," Fle said. "When I made it to my farm I realized, wow, I have Starlink. I can give people information. So that was my Base Camp One." With internet access, Fle began sharing updates on his social media accounts, posting videos of the flames, and sharing general updates. He would talk into his iPhone camera about where the front line was and what neighborhoods had gotten scorched, letting his followers know what was going on. He said a lot of people who saw that he was still in town messaged him on social media asking him to check on their homes and feed their animals. He spent the next several days driving from property to property, offering help wherever he could. With buckets of water and shovels stashed in his truck, he put out small spot fires igniting away from the main blaze. At one point, he even saved a coop of 19 chickens from the flames.

|

| This graphic shows the burn zones of the South Fork, Salt, and Blue 2 fires in Ruidoso, New Mexico, which occurred earlier this summer. The Blue 2 Fire started a month prior and was already contained by the time of the South Fork and Salt fires. | Photo: Wildfire.gov |

Austin Miller, another local who owns a septic, excavations, and fire-clean-up company in Ruidoso called Summit Operations, took to fighting the fire himself on the first night, using his company's water truck to spray houses to prevent them from catching on fire. He told me that he was up until 4 a.m. on Monday night trying to save people's homes, using his water truck to spray houses where fire was approaching. He was also using the water truck to fill up first responder fire trucks because the water system in Ruidoso had gone down, making it hard for them to extract water from fire hydrants. "There was volume but there was no pressure because the power went out and then the gas went out and it made it to where it was hard to get water, but we have a pump on our truck that we can do suction and pull water of ponds," Miller said. "We pulled water out of the ponds twice because we had sucked one of the tanks dry."

Miller and a few buddies protected multiple houses from burning and they supplied three fire trucks with water that ended up saving 30 to 40 houses or more. Although he didn't have enough water to spray houses that were currently on fire, he could spray the lawns, trees, and homes that hadn't burned yet to prevent the fires from spreading there. He described the situation as chaotic, saying they were "jumping from one house burning to the next," barely able to keep up with the spreading flames. It was a relentless effort: "spray this one, move 50 feet, start spraying here, and just keep trying to save the houses that weren't on fire." Monday night, in particular, stood out as the worst, with embers raining down and igniting spot fires behind them as they fought the flames in front. "It was total chaos—like Armageddon," Miller recounted.

|

| The forest surrounding Ski Run Road was decimated by the South Fork Fire. | Photo: Martin Kuprianowicz |

Crews and locals alike were working tirelessly to save their hometown. Exhaustion set in. Sleep-deprivation. Everyone was worked; hungry, sweaty, thirsty. Despite their valiant efforts, several of the Hotshots on Smokey Bear who live in Ruidoso would still end up losing their houses to the South Fork Fire. But everyone kept charging on. When Fle was sending updates from business owner Jasper Riddle's property, another Ruidoso local and business owner whose home is much closer than Fle's farm outside of town and who also had a Starlink system, he noticed three cases of sparkling water in his garage. That's when Fle found another way to make himself useful. After being badged as a First Responder by Downshift Brewing—a local brewery converted into an operations center providing free coffee and meals for first responders—he took the cases of water and drove to the crews to deliver refreshments. Later that week, Fle was asked by a friend who owned a car wash in Ruidoso to close the bay doors at his facility, and he noticed that there was a functional icemaker. Then the Hotshots started getting cold drinks. To boost morale, Fle placed an old mannequin in his truck bed named "Ken" that would accompany him on his runs. "Promote positivity. Give them a crisp high-five. A hug if they need it. Make a silly joke. Anything to get us out of our tension—tease the tension. That became so important because these guys were struggling," Fle said. He was working 17-18 hour days for a month straight, even after the fires were contained, dropping off supplies, meeting with residents, sorting through the rubble, and helping clean up damaged homes, which he was still doing at the time we sat down for our chat. "We're exhausted but we have to continue. It's my home," Fle said.

Downshift Brewing is a new brewery in the middle of Ruidoso that has a three-tiered balcony on its back that's surrounded by towering ponderosa pine trees and overlooks the Ruidoso River. It's constructed of wood giving it the appearance of a large log cabin. Eddie Gutierrez, the owner, opened its doors in August of 2021. Gutierrez is a tallish man with a dark goatee and long, jet-black hair that touches his shoulders. During the fires, Gutierrez stayed behind, keeping the doors to the brewery open to cook meals for first responders and residents alike. Gutierrez and his staff were whipping up to 600 meals a day, providing food to anyone who walked in. Fle, who had recently been working on the mural on the inside of the brewery, frequented Downshift, popping by several times a day. During the fires, he ran food and drinks from the brewery to the front line while Gutierrez and his crew worked hard on cooking.

"The whole community was affected by this fire. Everyone was evacuated. I turned my attention to trying to support the systems that were here as best I could. For us, that meant feeding people," Gutierrez told me.

|

| Downshift Brewing served as a hub for first responders to come get coffee, food, and use Wi-Fi during the Ruidoso fires. | Photo: Martin Kuprianowicz |

Those working in the kitchen that first week at Downshift were all volunteers—no one was getting paid, and they were working long days, often 12 hours or more at a time. "None of us were perfect, but we did the best we could," Gutierrez said. His brewery also had electricity and more importantly, Wi-Fi, at a time when all of the electricity in town was shut off. Gutierrez utilized this to share updates on the brewery's social media accounts of what he saw and how the community was responding—a move his wife convinced him to take. A lot of misinformation was circling at the time, according to Gutierrez. People were gossiping about how all of mid-town had been wiped out, that Albertson's was gone, or that there wasn't even a Ruidoso left, so he used his brewery's platform to share accurate information. It was a warm, sunny morning in mid-July when I met with Gutierrez at the brewery, and the National Weather Service had issued a flood warning for later that afternoon. Seemingly everyone I spoke to that morning in Ruidoso was planning their day around the flood warning, nonchalantly, almost with a mild sense of humor or lightness attached to it, cracking small jokes about having to escape the incoming floods. Yet no one was mistaken; what was happening later that day would be purely devastating.

|

After the wildfires were contained, the monsoon came, bringing with it flash floods that were almost as devastating as the fires themselves. This Ruidoso neighborhood was devasted by the flooding. | Photo: Austin Miller

|

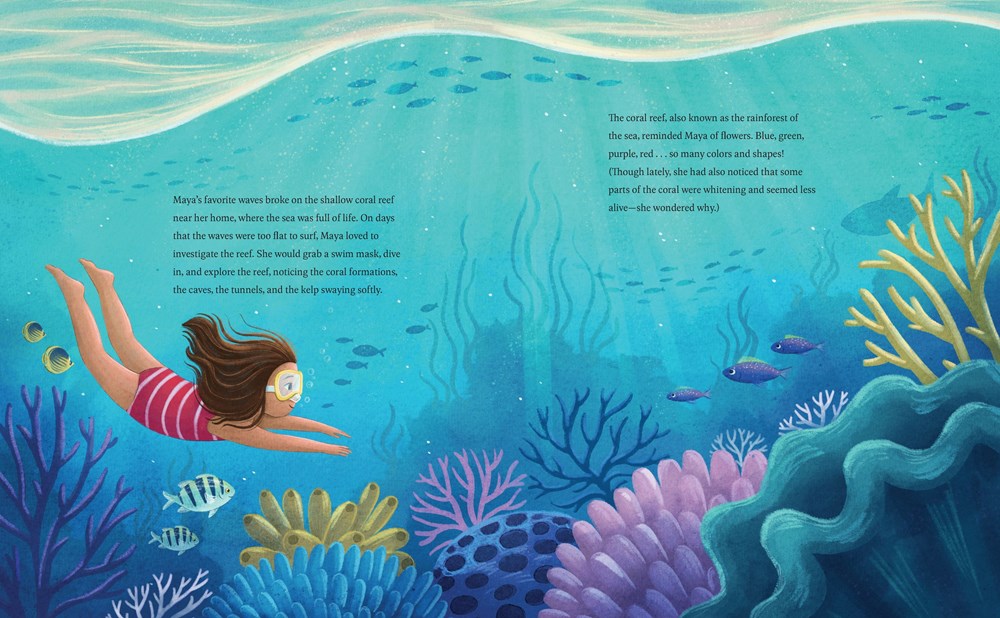

By the first weekend after the fires started, they had been mostly contained. Structures were no longer burning down thanks to diligent work from Hotshots, a break in the winds, and some much-needed rainfall that arrived mid-week. The town was closed to the general public until Sunday, June 23, when Mayor Crawford

lifted the evacuation order, first allowing full-time residents to come back in before permitting all of the general public, including visitors, the following week. Early in the afternoon of June 27, after both the South Fork and Salt fires had been 99% contained, Fle had come upon a team of flood specialists from a Burned Area Emergency Response team sent by the Forest Service walking out of

Cedar Creek, which is north of Upper Canyon where the South Fork Fire initially started. Cedar Creek sustained some of the most ferocious devastation from the blaze with thousands of acres of old-growth forest, hundreds of houses, dozens of hiking and mountain bike trails, and an array of National Forest infrastructure completely wiped from the face of the earth. Fle told me that he tried to give the flood specialists some snacks and cold drinks but they wouldn't accept them. They looked solemn. After a brief conversation, they expressed relief that the fires were over but said that what they had witnessed in Cedar Creek and Upper Canyon was so disturbing it had ruined their appetite. They knew what would happen once the rains came.

Monsoon season in the Southwest typically occurs from July to September. It's a seasonal weather pattern that brings with it thunderstorms and elevated rainfall, particularly affecting areas such as Arizona and New Mexico, but also extending to parts of western Texas, southern Colorado, Utah, Nevada, and occasionally southern California. Despite the containment of the fires, the aftermath was far from over. The monsoon rains caused flooding, exacerbating the situation, as the soil burned by the fires had become weak and unable to absorb moisture. That, combined with Ruidoso's steep terrain that undulates through and around the town, was another invitation to chaos. The first big rain storms that rolled in brought with them floodwaters that had reportedly reached as high as 12 feet in some areas, causing further destruction and displacing even more residents. Highway 70, a major route, constantly flooded, and there were over 100 swiftwater rescues by mid-July. One video that emerged from Ruidoso showed an 18-wheeler truck overturned by a flash flood on Highway 70 with its driver still inside.

Another one of Fle's friends, who owns a bookstore in a lowlands area of Ruidoso, was caught in a torrent of fast-moving water as it broke in through the doors of her bookstore. She was pinned against a wall and couldn't move, suffering minor injuries. Fle continued documenting the devastation despite the emotional toll it took on him, often breaking down in his truck after witnessing the destruction of his hometown. At one point, he called his business partner, James Flores, in tears. Flores urged him to keep filming for the world to see. Fle then stepped back out of his truck, donned his muck boots, and trudged through the muddy, contaminated water to capture more footage of the aftermath.

|

| Flash floods with water levels reaching 12 feet were reported in some low-lying parts of Ruidoso after the fires were contained and the rains came. | Photo: Austin Miller |

"It's something that nobody is prepared for," Austin Miller said, who was working on clean-up efforts at the time we spoke on the phone at the end of July. "I've seen houses get torn apart because of so much water. Cars, full garbage dumpsters floating down in a river," he said. The fires destroyed over 1,000 homes and the floods added to the toll, with over 200 more homes damaged by late July. The community rallied to clean up and rebuild, but the waiting game with federal aid was frustrating.

"I don't know if we'll be here six months from now," Gutierrez said. "All of Ruidoso is an industry driven by tourism. Even if anybody isn't directly employed by tourism, they are somehow associated with it."

Downshift Brewing, a new business and popular social hub with weekly live music before the fires, was now struggling to make ends meet. June and July are the biggest months for business in Ruidoso, holding over most everyone until Labor Day. Profits from Labor Day Weekend then hold businesses over until Christmas, when ski season kicks off. Gutierrez urged his workers to claim unemployment, but Disaster Unemployment Assistance hadn't kicked in. "Everybody's going through this crisis even if your house didn't burn or flood," Gutierrez said. "We're trying to avoid financial instability as best we can." Like the majority of Ruidoso's business owners, Gutierrez was literally trying to stay above water.

Jasper Riddle is another local who's been a part of Ruidoso's business community for over 30 years and is the owner of Noisy Water Winery and a few other businesses in town. When I spoke with Riddle on the phone it was exactly one month after the fires started and he was "knee-deep" in insurance claims for his enterprises that were impacted. There was another flash flood risk issued for Ruidoso that day.

"We need a lot of damn help," Riddle said. "It's not bottles of water and thoughts and prayers; it's people showing up to help rebuild. It's money. It's infrastructure. It's tourism."

Collin Hood, a long-time friend and business partner of Riddle, lost his ski shop and cannabis dispensary while half of his home burned down, all within four hours of one another. Swiss Chalet, a long-time-standing hotel in between mid-town Ruidoso and Ski Run Road leading to the ski area, was caught in the direct line of the South Fork Fire and was burned to the ground. Nothing from the iconic hotel survived. "The businesses are getting kicked in the face right now," Riddle said. At the time I spoke with Riddle, the only financial aid available for the Ruidoso economy was disaster relief loans from the Small Business Administration. He talked about how COVID was rough for Ruidoso and how they had just barely started to pull back out of the weeds from it this year. But that was a global crisis—this time it was only the people of Ruidoso who were suffering.

Despite the devastation, the people fight on. Fle organized a fundraiser, raising over $150,000 for fire victims through Venmo, silent auctions, and partnerships with other tattoo shops. "Absolutely all of the money will be going toward the Ruidoso community," Fle said. "We want to see how much we can raise for those who lost their homes." Fle’s efforts extended beyond financial support; he also organized a silent auction featuring paintings donated by local artists, raising $19,000 from the event alone. Additionally, eight other tattoo shops in El Paso and New Mexico partnered with Fle, contributing to the total funds raised. "Now people have realized what stronghold our outreach is, creating positivity, giving back, giving thanks to the people," he said with tears in his eyes as he talked about the community's response. "You got to look for the good things. And be a good neighbor."

|

| The author’s father’s home (pictured) was burned to the ground by the South Fork Fire, along with the rest of Ruidoso’s Alpine Village neighborhood. | Photo: Martin Kuprianowicz |

The South Fork and Salt Fires together burned a staggering 25,508 acres and destroyed over 1,400 structures. According to Miller, the damages brought by the fires and floods will end up costing over $1 billion. The official cause of the South Fork Fire was a lightning strike, according to a report shared by the U.S. Department of Agriculture. Lightning is a common natural cause of wildfires, particularly in areas like New Mexico, where dry conditions and thunderstorms frequently coincide. According to the National Interagency Fire Center, lightning accounts for about 60% of all wildfires in the United States, with New Mexico being particularly susceptible due to its climate and topography. The state experiences thousands of lightning strikes annually. While the South Fork Fire was a natural disaster, the Salt Fire was determined to be human-caused.

FBI agents have identified a man and a woman as suspects in the Salt Fire, as well as several other fires on the Mescalero Apache Reservation. According to court documents, the suspects were linked to the fires through a vehicle seen fleeing at least five other fire scenes and shoe prints left at the Salt Fire site. A federal search warrant application, filed by an FBI agent in New Mexico on July 11, sought to obtain a pair of Vans shoes belonging to the female suspect. The warrant was executed on July 15. Although the El Paso Times has chosen not to disclose the names of the suspects, as they have not been formally charged, the warrant details that between May 3 and June 18, there were 16 wildfires in the Mescalero Apache Reservation believed to be human-caused. The man and woman named in the warrant have been linked to at least six of these fires. The investigation into the Salt Fire and other suspicious fires in the area continues as authorities work to gather more evidence and potentially bring charges against the suspects.

|

To boost morale, Fle placed an old mannequin named "Ken" in the bed of his truck to keep him company during his runs. | Photo: Martin Kuprianowicz

|

The road ahead for Ruidoso is long and fraught with challenges. The response from government agencies has been a mix of immediate action and bureaucratic delays. While the initial firefighting efforts were swift and coordinated, the distribution of financial aid and resources has been slower. The Burned Area Emergency Response team has been assessing the damage and planning for flood prevention, but the community is still waiting for substantial federal aid. With damages estimated to be over $1 billion, Jasper Riddle has been advocating for more proactive government intervention. "That's a lot of damn money you need to get moving really really rapidly in order to get people to start to feel normal again." The community's determination is also evident, but the support of tourists and the broader public will be crucial in the town's recovery since tourism is the town's lifeline. It needs people to come back and support its businesses. Riddle added that it's not only about the immediate financial support but also about rebuilding their reputation as a destination. "We need to show the world that Ruidoso is still here and still beautiful," he said. However, both Gutierrez and Riddle recognize the delicate balance between encouraging tourism and ensuring responsible visitation. "People need to come back in responsibly and understand their surroundings and be aware," Riddle said."That's the negative externality associated with wanting to live so close to nature."

Riddle emphasized that visible progress—for people to actually see work getting done to rebuild Ruidoso—is crucial for restoring a sense of normalcy in the community. Riddle says people are already bouncing back in more beautiful ways than he could ever imagine. He recounted how one local, whose home was destroyed by the fire, had already started planting trees on his former property. "He's like, 'Well, I can't build a house yet, but I can get some trees in the ground.'" The people of Ruidoso are trying to get back on the mend. A strong winter tourism season will likely aid in the economic recovery, which is something Riddle—like all Ruidoso business owners—is desperately hoping for, but none of them are thinking that far ahead yet. They are trying to make ends meet right now; to keep their staff's payroll flowing and their livelihoods secure. Amidst the loss from the fires and floods, Riddle does see some signs of hope, like how the recent rains have caused green grass to sprout on the site where Swiss Chalet once stood. "If it wasn't for the fires, this would be one of the most beautiful summer seasons I've seen." This regurgitation of life is an indication that they, too, as a community can grow back.

|

| An elk grazes outside of Downshift Brewery in mid-town Ruidoso. | Photo: Martin Kuprianowicz |

One positive aspect of such a destructive fire, Riddle thinks, is that much of the damage occurred near existing infrastructure. This makes the recovery efforts much easier than if a wildfire of similar size occurred in a remote location, far from roadways. The fire, perhaps, could allow a clean slate for Ruidoso. "It gives you the opportunity to come back in and build better. To build better master-planned areas. It's just a matter of having the resources to do so." Riddle hopes that each day brings a bit of improvement and that they make small progress every day. "I hope in six months we look back and say, 'Oh my God, it doesn't even look like something happened.'"

Looking ahead, the path to recovery is clear but challenging. The community needs continued support from government agencies, financial aid, and, most importantly, the return of tourists. The rebuilding efforts will take time, but the personal stories of resilience from the people of this ski community crystalize and make known the spirit of Ruidoso, New Mexico—a place where tall, powdery peaks collide with big, open ranches with livestock surrounded by herds of wild horses and elk; where cowboys and skiers mingle, share stories, have cookouts, build friendships, and start families. Where ancient indigenous culture dances with proud Southwest tradition. The courageous Hotshots who worked day and night to put out the fires, the pilots dropping slurry left and right, Logan Fleharty's efforts to use his Starlink system for communication, Austin Miller's late-night firefighting with his water truck, Eddie Gutierrez's kitchen staff providing thousands of meals a week and his PSAs to clear up misinformation, and Jasper Riddle's strong voice in the community to get tourism back up and running—these are but some of the countless stories of the brave souls who have given their time and energy and health to help their neighbors in any way they know how. The light shone from these vicious fires has illuminated the truth of a town that refuses to give up. "It's moments like these that show the true strength of our community," Fle said. "We are down but we are not out."

Nobody in Ruidoso is the same as they were the day before the fires. They probably won't be for a long time, either. Yet hope still remains, like a seed sprouting in the fire-scorched soil, reaching for the sun despite the odds. "It's still a beautiful place. I still love this place and I still believe in it. You could come to Ruidoso today and have a great experience. We are going to continue to focus on healing this place in any capacity that we can. If we're going to make it, we're going to make it because the whole place is stronger. And if we fail—we're going to fail trying," Gutierrez told me, teary-eyed, as we were wrapping up our chat at the brewery. It was approaching mid-day and the sun was still shining but clouds were starting to form in the distance; tall, white, puffy, ethereal castles amidst a sea of azure sky. They floated nearer, silently, ever so gently yet ominously toward this little mountain town of heroes. Their life-giving water would soon turn the ashes left behind from the fires into deadly, earth-devouring waves. Like Ruidoso, it will be from these same ashes that a phoenix rises.

|

| In the wake of the fires, Fle and his mannequin companion, Ken, became symbols of hope and support for first responders. Photo: Martin Kuprianowicz |

Ruidoso Wildfire Relief Fundraisers